Table of Contents

- Why Is Everyone Watching The Fed?

- Why the Fed Cuts Rates

- How Rate Cuts Work

- Who Benefits First: Stock Markets

- Who Waits: Ordinary Households

- The Irony of Rate Cuts

- Why the Fed Uses Core Measures

- The Household Experience: Incomes vs. Prices

- What Should Households Watch For?

- The Broader Dilemma

- September 17th

- But Will Rate Cuts Prevent A Recession?

Why Is Everyone Watching The Fed?

All eyes are on the Federal Reserve this month. Markets, analysts, and the media expect the Fed to lower interest rates in the FOMC meeting on September 16-17th. The move will be headline news. The bond market has already ‘priced in’ the reduction. Stock investors are betting on a rise in asset prices..

But for most regular families, the real question isn’t what happens to the S&P 500. It’s simply: what does this actually mean for me? Will a rate cut ease the pressure on household budgets, make debt payments cheaper, or finally bring down the cost of living?

The answer is a bit complicated. Although rate cuts can stabilise the economy, they don’t always translate into immediate relief for households. In fact, the first beneficiaries are often financial markets and large corporations. Regular families often need to wait much longer.

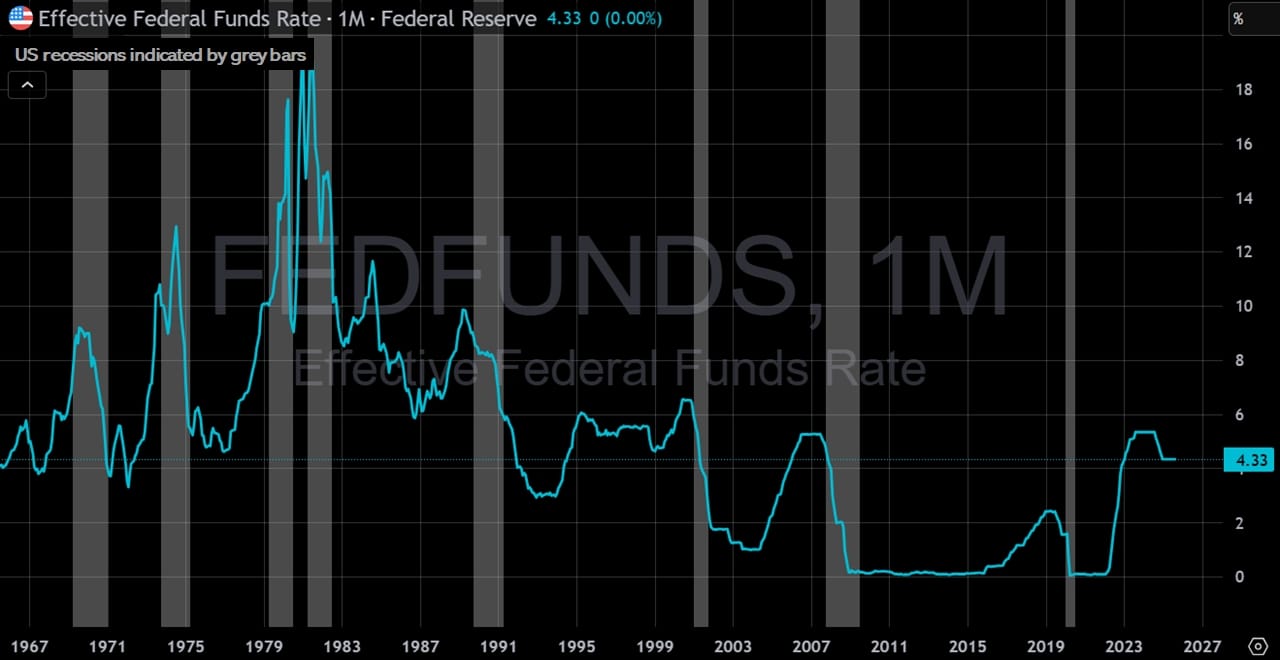

Chart: US Federal Reserve Funds Rate

Why the Fed Cuts Rates

The Federal Reserve’s job is to keep inflation low and stable, while supporting maximum employment. Since 2022, its primary focus has been the first part. Inflation surged after the pandemic, hitting levels not seen in 40 years. To cool demand, the Fed raised rates at the fastest pace since the early 1980s.

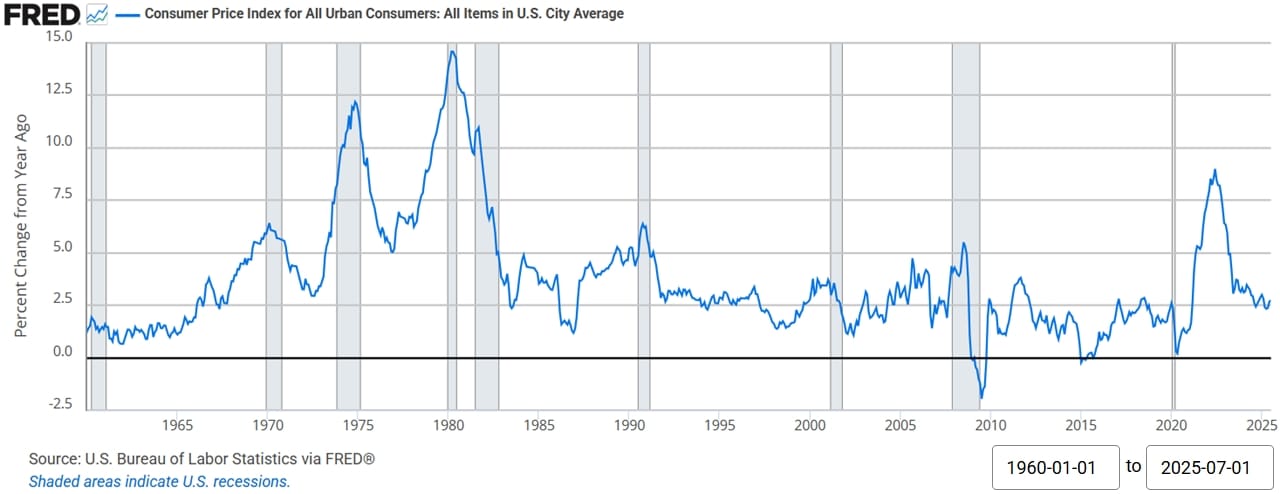

Chart: US CPI Index - Year on Year Percentage Change

Now that inflation has eased significantly - headline CPI is running at about 2.7% year-on-year, and core PCE (the Fed’s preferred gauge) is around 2.5%.

Meanwhile, the labour market shows signs of strain:

- Unemployment has climbed to 4.3%, the highest in nearly four years.

- Job growth is slowing sharply: only 22,000 new jobs were added in August, and earlier months have been revised down.

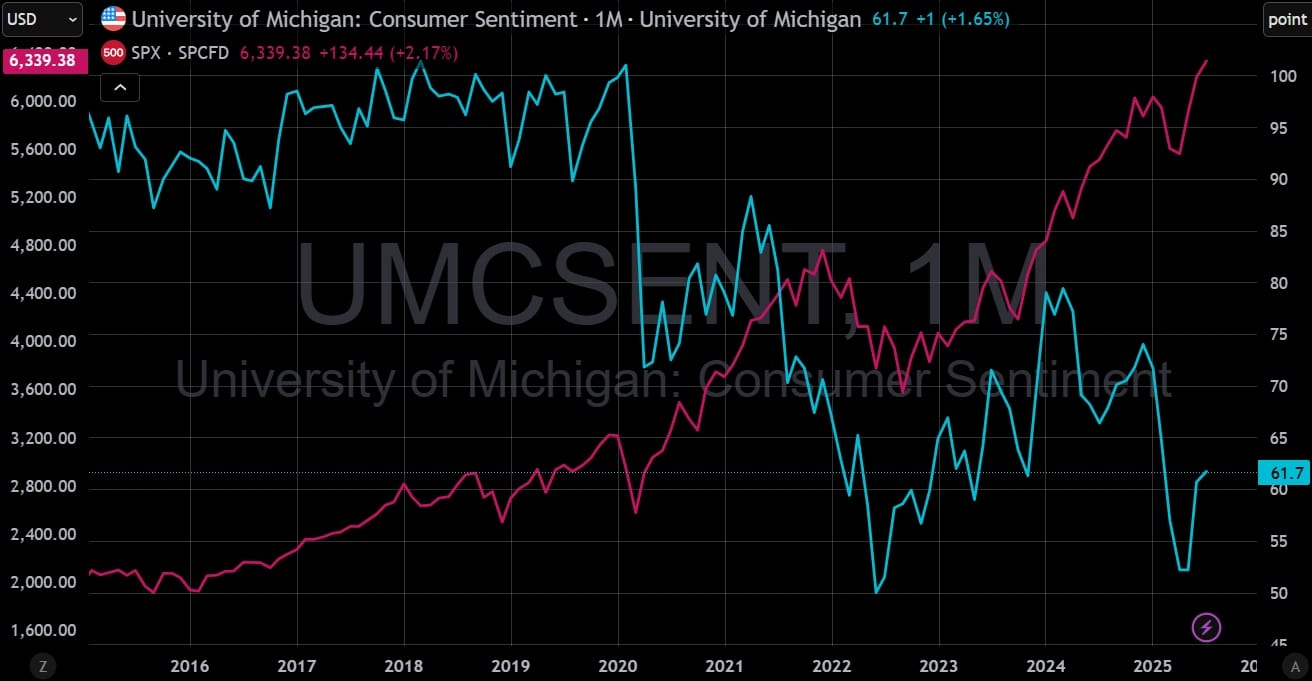

- Consumer sentiment is weakening, with surveys showing households worried about their financial outlook.

With inflation reduced and growth cooling, the Fed now has scope to attend to the second part of their job. Cutting interest rates is meant to lessen risk of a hard recession, ease credit conditions, and support job creation.

How Rate Cuts Work

By lowering the policy rate, the Federal Reserve reduces the cost of short-term borrowing across the financial system. The effects filter through the economy in several ways:

- Business investment

Companies can refinance debt or borrow more cheaply to expand, hire, or acquire. - Higher asset valuations

Stock and bond markets tend to rally as lower rates make future profits more valuable and borrowing costs cheaper. - Weaker U.S. dollar

A lower interest rate relative to other countries makes the dollar less attractive, boosting exporters but potentially raising import costs. - Cheaper credit for households

Mortgage rates, auto loans, and credit card interest rates may drift lower over time, but not always immediately.

In theory, these effects support both the financial system and the real economy. But in practice, the timing and distribution of benefits is uneven. The big dogs are first to the bowl...

Who Benefits First: Stock Markets

Financial markets respond instantly. The moment the Fed signals a cut, bond yields fall and equity markets surge. Large-cap technology firms - the “Magnificent 7” (Apple, Microsoft, Amazon, Alphabet, Meta, Tesla, Nvidia) - benefit disproportionately. Their valuations are based on future earnings streams, which look more valuable when discounted at lower rates.

Corporations with significant debt loads also benefit. Refinancing becomes cheaper, balance sheets look healthier, and share buybacks or acquisitions can be funded at lower cost. Investors feel wealthier, and risk appetite increases.

For Wall Street, the impact of a Fed rate cut can be measured in hours and days.

Who Waits: Ordinary Households

The picture is different for households under pressure.

A September rate cut won’t change the grocery bill, the rent, or health insurance premiums.

Credit cards may remain at 20% APR or higher, even if Fed rates edge lower. Auto loans and mortgages may come down slightly, but refinancing remains out of reach for many families who took on debt at higher levels or face tighter lending standards.

The real benefit for households is employment stability. If lower rates succeed in supporting business confidence and preventing layoffs, that helps families indirectly by keeping incomes secure. Unfortunately, this takes time. The household experience of a rate cut arrives in quarters and years, not days.

The Irony of Rate Cuts

There’s a sharp irony - a policy tool designed to stabilise the whole economy delivers its first and largest benefits to those least in need. Wealthy households and large corporations - already buffered by assets - gain rapidly. Meanwhile, middle- and low-income families see little immediate relief to their financial stress.

The result is a two-tier dynamic:

- Stock markets rally overnight.

- Household relief, if it comes, arrives slowly and unevenly.

This gap explains the persistent credibility challenge facing the Fed. Households hear policymakers say “inflation is under control,” yet daily life still feels expensive.

Chart: S&P 500 Makes New Highs While Consumer Sentiment Languishes in Warning Zone

Why the Fed Uses Core Measures

Part of the disconnect arises from how inflation is measured. The Fed emphasizes core PCE inflation, which strips out food and energy. These items are enormously important to households – but they are volatile and generally driven by factors outside the Fed’s control (oil prices, weather shocks, geopolitical events).

Core inflation is meant to capture the “sticky” elements of pricing: rent, healthcare, education, services. These are slower to change but reveal whether inflation is embedding in the economy.

For households, though, it’s headline inflation (CPI) - the grocery basket and the fuel pump - that shapes sentiment. This is why consumers feel squeezed even when the Fed crows about progress.

The Household Experience: Incomes vs. Prices

Another way to understand the issue is through real income. Inflation may be easing on paper, but household incomes have not surged to match. Wage growth is modest, and when adjusted for inflation, the average family feels worse off than before the pandemic.

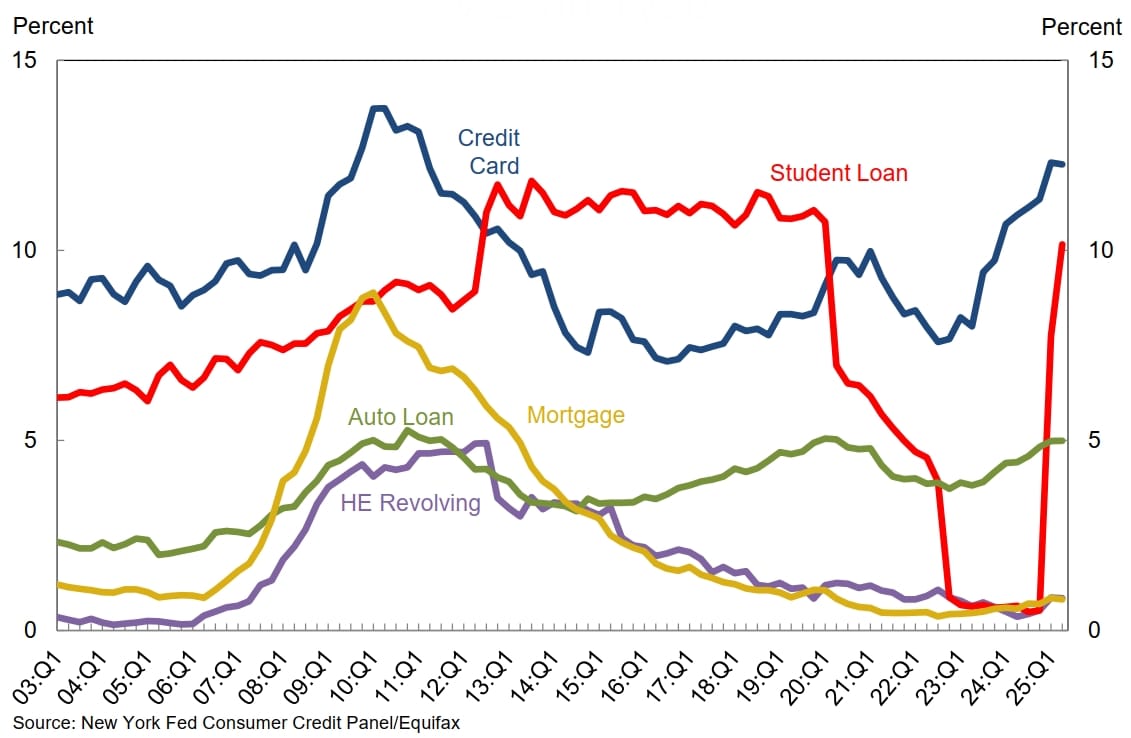

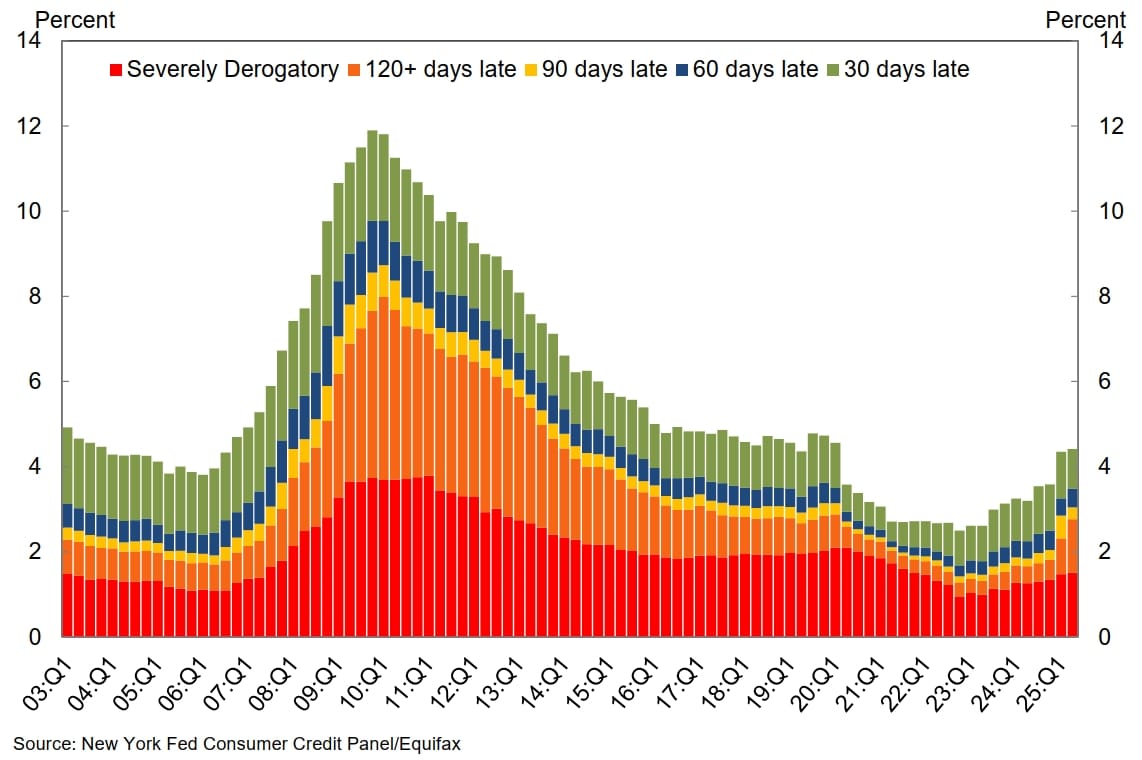

At the same time, borrowing costs remain high, with credit card delinquency rates rising - 12 percent of credit card balances (which total $1.2Bn) are more than 90 days overdue. Car loan stress is mounting. Inflation is “under control” partly because households have been forced to cut back. In other words, demand has weakened not just from Fed policy, but from household fatigue.

Chart: US Household Total Debt Delinquency Balance by Status

What Should Households Watch For?

If the Fed cuts rates in September, families can realistically expect:

- Increased employment security: The biggest benefit is if rate cuts prevent job losses. As long as the labour market holds, households have a buffer.

- Gradual easing of credit costs: Mortgage and loan rates may drift lower over time, especially if more cuts follow. Credit card rates are slower to adjust.

- Housing supply response: Lower rates may encourage new construction, eventually easing rental pressure; but this is a slow process.

- Government borrowing: Lower rates reduce the government’s interest burden, freeing more of the budget for programs that support households. Though this benefit is indirect and long term.

But none of these deliver immediate relief at the checkout counter.

The Broader Dilemma

The Fed’s task is unenviable. It must balance two realities:

- Financial markets are highly sensitive to rate changes, amplifying benefits for investors.

- Households are less sensitive in the short term, particularly lower-income families with limited credit access.

The paradox is that easing designed to protect households may reinforce inequality in the short run. Markets celebrate; families wait.

September 17th

The Federal Reserve will most likely reduce interest rates this month. That decision will be framed as a win for households, a step toward stability, a sign that inflation is “under control.” Which is true, in a way. Rate cuts help prevent recessions, support employment, and keep the economy from seizing up.

But the immediate impact on the average household is limited. Relief at the supermarket or the petrol station doesn’t come from monetary policy. Credit card rates won’t suddenly halve. For many families, the cost of living will still feel punishing. The real benefits only come if jobs are preserved and borrowing costs gradually ease.

But Will Rate Cuts Prevent A Recession?

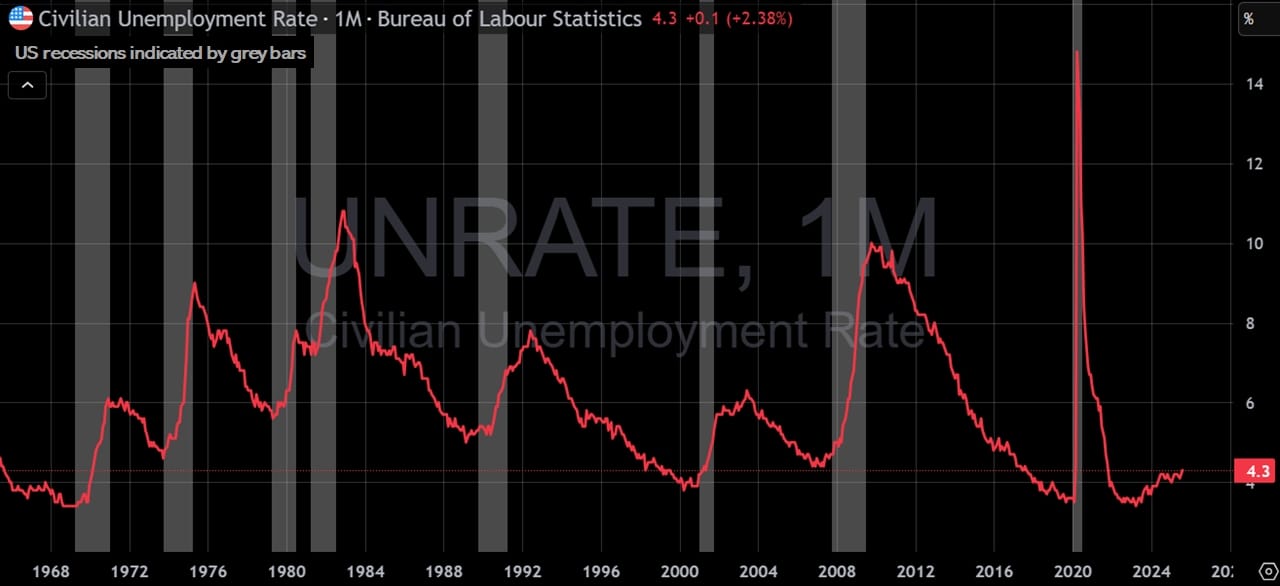

The extent to which rate cuts preserve jobs is crucial for the national economy. Historically, recessions in the United States have always coincided with a significant rise in unemployment. When joblessness rises sharply, downturns follow.

Consumer spending accounts for about two-thirds of GDP, which means the health of the economy depends on household confidence and purchasing power. When families feel squeezed - even if headline inflation looks “under control” - the broader growth picture inevitably weakens.

Take a look at the chart below. Every grey recession bar is paired with a visible spike in unemployment. The lesson is simple:

If rate cuts succeed in stabilising jobs, a recession may be avoided. If not, history suggests the risks are rising.

Chart: US Unemployment Rate with Historical Recessions

Given the lag between monetary policy and jobs, the Trump administration’s impatience for rate cuts may not have been entirely misplaced.